Brief History

- HOME

- ABOUT

- GOVERNMENT

- SERVICES

- BUSINESSES

- CAREERS

- DIRECTORY

- EMPLOYEES

- TRIBAL MEMBERS

- VISITORS

- DONATION REQUESTS

The Muh-he-con-ne-ok

The People of the Waters that Are Never Still have a rich and illustrious history which has been retained through oral tradition and the written word.

Our many moves from the East to Wisconsin left Many Trails to retrace in search of our history. Many Trails is an original design created and designed by Edwin Martin, a Mohican Indian, symbolizing endurance, strength and hope. From a long suffering proud and determined people.

Origin and Early History

In the early 1700's, Hendrick Aupaumut, Mohican historian, wrote that a great people traveled from the north and west. They crossed waters where the land almost touched.* For many, many years they moved across the land, leaving settlements in rich river valleys as others moved on.

Reaching the eastern edge of the country, the Mohicans settled in the valley of a river where the waters, like those in their original homeland, were never still. They named the river the Mahicannituck and themselves the Muh-he-conneok, the People of the Waters That are Never Still. The name evolved through several spellings including Mahikan. Today, however, they are known as the Stockbridg-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians. Others of these Lenape people chose to settle on the river later renamed the Delaware, and are sometimes called Delaware Indians.

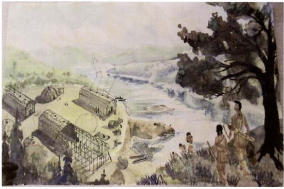

Because the Mohican people chose to build their homes near the rivers where they would be close to food, water and transportation, they were sometimes called River Indians. Their homes, called wik-wams (wigwams), were circular and made of bent saplings covered with hides or bark. They also lived in long-houses which were often very large, sometimes as long as a hundred feet. The roofs were curved and covered with bark, except for smoke holes which allowed the smoke from fire pits to escape. Several families from the same clan might live in a longhouse, each family having its own section. The family clans of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band were the bear, the wolf, the turtle,and the turkey.

The Mohicans' lives were rooted in the woodlands in which they lived. These were covered with red spruce, elm, pine, oak, birch and maple trees. Black bear, deer, moose, beaver, otter,bobcat, mink and other animals thrived in the woods, as well as wild turkeys and pheasants. The sparkling rivers teemed with herring, shad, trout and other fish. Oyster beds were found beneath the river's overhanging banks for some distance up the Mahicannituck. Berries and nuts were abundant. It was a rich life.

*According to John W. Quinney, Hendrick Aupaumut commited the oral history of the Mahicans to writing. in the mid-1 l00's, a nonIndian took the manuscript to be published and it was reportedly lost. When found, the manuscript's first page was missing. Two versions of the manuscript exist: one in the Massachusetts Historical Collection and one in Electa Jones' book STOCKBRIDGE PAST AND PRESENT. What is meant by the "north and west''and "waters where the land nearly touched''is not known. The Bering Strait theory is question-able, based on current research.

Mohican women generally were in charge of the home, children and gardens, while men traveled greater distances to hunt, fish or serve as warriors. After the hunts and

harvests, meat, vegetables and berries were dried. These along with smoked fish were stored in pits dug deep in the ground and lined with grass or bark.

During the cold winter months, utensils and containers were carved, hunting, trapping and

fishing gear were repaired, baskets and pottery were created, and clothing was fashioned and

decorated with color- fully dyed porcupine quills, shells and other gifts from nature.

Winter was also the time of teach- ing. Storytellers told the children how life came to be, how the earth was created, why the leaves turn red, and so on. Historians also related the story of the people: how they learned to sing, the story of their drums and rattles, what the stars could teach them. Children learned the ways of the Mohica.ns, their extended family: how to relate to each person, as well as to all the gifts of the Creator, and how to live with

respect and peace in their community. They also learned that they had responsibilities, so they began to learn skills.

In early spring, the people set up camp in the Sugar Bush. Tapping the trees, gathering the sap and boiling it to make maple syrup and sugar was a ceremony welcoming spring. There were many ceremonies during the year wheneversomething needed special"paying attention to,"such as the planting of the first seeds - the corn, beans and squash - and the time of harvest.

As the Mohican people increased their territory across the Eastern seaboard, they became affiliated with the Munsee, who were also part of the Lenni Lenape people. The Munsees had settled near the headwaters of the Delaware River, near the Mohicans, and their language and lifestyles were very similar.

MOHICAN/MUNSEE TERRITORY

The Mohican/Munsee lands extended across six States from southwest Vermont, the entire

Hudson river valley of New York from Lake Champlain to Manhattan, western Massachusetts up to the Connecticut River valley, Northwest Connecticut, and portions of Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

The Mohicans never forgot that they were relatives of many other tribes who had traveled with them over the centuries. Mohican leaders often sent warriors to assist their allies when they were in danger of being attacked. But these were temporary alliances and did not result in a powerful confederacy such as that of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois.

THE COMING OF THE EUROPEANS

In September 1609, Henry Hudson, a traderforthe Dutch, sailed up the Mahicannituck into

the lands of the Mohicans. He found himself in an area rich in beaver and otter, the kinds of furs the Dutch most coveted. By 1614 a Dutch trading post was established on an island later named Castle Island.

As the fur trade expanded and furs became more difficult to find, tensions developed between the Mohicans and the Mohawks, Haudenosaunee people to the west. Each group wanted to

maintain its share of the fur trade business, as well as retain friendly relations with their European allies. Not only did conflicts occur between the Mahicans and the Mohawks, but the Native people also were caught in wars among the Dutch, English and French. The Mohicans were eventually driven from their territory west of the Mahicannituck. In the early 1700's, indebtedness, questionable land purchases and cultural conflicts caused them to move farther east near the Housatonic River in what were to become Massachusetts and Connecticut.

The Mohican economic pattern was greatly changed by contact with the Europeans. They stopped making many traditional items because newtools, iron kettles, cloth, guns and colorful glass beads were available at the trading posts. The English, who eventually replaced the Dutch in this area, chose to "civilize" all the Native people in what they called"New

England." The vast lands, which the Mohicans had used for gardens, hunting and fishing, began to have boundary lines and fences when shared with non-Indians. Since their lands were declared to belong to European monarchs by"right of discovery," they found that they could not defend their ownership in the courts of the colonists. As more and more

Europeans arrived, the Mohicans, like other Native people who had traditionally depended upon themselves and the resources of Mother Earth, found themselves dependent on white people and what they could provide.

The coming of the Europeans into the lands of the Mohicans affected them in another catastrophic way. Europeans brought diseases with them: smallpox, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever. Native people, unfamiliar with these diseases, had not built up an immunity to them, and hundreds of thousands - sometimes whole villages at a time - perished. These diseases greatly decreased the numbers of Mohicans.

European Christians with missionary zeal also entered Native villages for the purpose of converting the people from their traditional spiritual practices to Christianity. Some Native people, noting that the Europeans seemed to be prospering in this new land, felt that perhaps the Europeans' God was more powerful, and agreed to be missionized. In 1734, a missionary named John Sergeant came to live with the Mohicans in their village of Wnahktukuk. He earnestly preached the Christian religion, baptized those who accepted his·teaching, and gave them Christian names such as John, Rebekah, Timothy, Mary and Abraham.

John Sergeant is depicted here meeting with Chief Konkapot

In 1738, the Mohicans gave John Sergeant permission to start a mission in the village. Eventually, the Euro- pean inhabitants gave this place the name "Stockbridge," after a village in England. It was located on the Housatonic River near a great meadow bounded by the beautiful Berkshire Mountains in western Massachusetts. ln this mission village, a church and school were built. Other people who wished to hear the missionaries' teachings also came to live in the village. Some of these were the Wappingers, the Niantics, Brothertons, Tunxis, Pequot, Mohawk, Narragansetts and Oneidas. As some of these tribes merged with the Mohicans, the tribal group came to be known as the Stockbridge Indians.

Between 1700 and 1800, European countries battled for control of the land called America. The French and Indian Wars were really conflicts between England and France over territories they had taken from the Native people who were recruited to help them fight. The Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 were fought between the American colonists and England. The

"Americanized" colonies no longer wanted to be governed by the Mother country. The Stockbridge Mohicans, as well as the Oneida, Tuscarora and other Native warriors, supported the colonists in their revolution. In one battle, the Battle of Van Cortlandt's Woods, a number of Stockbridge Mohicans lost their lives.

When the surviving warriors returned home, they discovered that their lands were lost through mortgage and debt, and often fraudulent means, and that plans had already been made to remove them from Stockbridge. The lives of the Mohican people were drastically changed by the fur trade, European missionaries, disease and war.

This was the home of the missionary. the Rev. John Sergeant

All of these worked together to cause a breakdown in their traditional Mohican life and beliefs. Some still practiced spiritual ceremonies secretly, as these customs were frowned upon by the missionaries, but at the same time many European customs were adopted. Fewer and fewer of the people spoke the Mohican language; thus their thought patterns about the natural world were altered. The ancient arts of basket- and pottery-making continued, but other seasonal occupations were abandoned. In order to survive, the Stockbridge Mohican adopted the trades and behaviors of their non-Indian neighbors: farming, lumbering, worshipping in church, sending their children to schools. But as the eighteenth century neared its last twenty years, their lives were to change even more drastically.

REMOVALS WESTWARD

It became apparent after the Revolutionary War, with their numbers greatly reduced and intruders (called"settlers") using unscrupulous means to gain title to the land, that the Stockbridge Mohican people were not welcome in their own Christian village any longer. The Oneida, who had also fought for the colonists in the war, offered them a portion of their rich farmland and forest.

The Stockbridge Mohican accepted the invitation and moved to New Stockbridge, near Oneida Lake, in the mid-1780's. Again they cleared forests and built farms. A school, church, and sawmill were built.

The tribe flourished under the leadership of Joseph Quinney and his counselors.

But land companies, desirous of making profits from the land, proposed that New York State remove all Indians from within its borders. The pressure for removal was great. John Sergeant recorded in his joumal of August 1818,"About onethird of my church and one-fourth of the tribe (70 souls) started from this place for White River." Their leader, John Metoxen, led the group to the White River area in what is now Indiana to settle among their rela-tives, the Miami and the Delaware. When they reached their destination, after about a year, they found that the Delaware had already been coerced into selling the land.

Meanwhile, missionaries, agents from the state of New York and commissioners from the War Department were negotiating with the Menominee and Ho- Chunk (Winnebago) for a large tract of land on which to relocate the New York Indians in what is now Wisconsin. A treaty was negotiated in 1822. The Stockbridge Mohicans were on the move again. The group that had traveled to Indiana with John Metoxen were the first to arrive, and they began to build a village on the Fox River at Grand Cackalin (Kaukauna), also called Statesburg. For the next several years, those who had remained in New York followed, traveling by foot, wagon or sometimes steamship on the Great Lakes.

Electa Quinney

Perhaps the first English-speaking people in the state were in the John Metoxen group. Electa Quinney, the first public school teacher in Wisconsin, was a Stockbridgelndian woman. The first Protestant minister, as well as the first Christian Temperance Union, came with the Stockbridge Mohican people. Again they established a church and a school.

But adopting the white man's religion and education did not assure acceptance. As long as Native people held land, they were subject to removal. As soon as the Fox River was perceived to be a major water-way, forces prevailed upon the Menominee to reconsider their negotiations. After final negotiations, the Oneida settled in the Duck Creek area. The Stockbridge and Brotherton were moved to areas on the east shore of Lake Winnebago in 1834.

Meanwhile the federal government was forcing Indian nations to agree to land session treaties, often physically moving them to lands far distant and different from their original homelands. In 1832, Congress had enacted President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act by which all Indians from the east would be moved to lands west of the Mississippi River.

A group of Stockbridge Mohicans, fearing the inevitable, moved to Indian territory in 1839. Many died while making this journey. Some reached Kansas and Oklahoma and married into other tribes. Most simply gave up and returned to Wisconsin, which had gained statehood in 1848.

During this period a group of Lenni Lenape/Munsees joined their relatives, the people at Stockbridge, Wisconsin, and were accepted into the community. Known at first as the Stockbridge and Munsee, eventually this community was simply called the "Stockbridge-Munsee."

The federal removal policy caused dissension among the people who remained in Wisconsin, which led to political divisions in the tribe. Presented with the opportunity by government agents, some Stockbridge people relinquished their Indian status and became taxpaying citizens of the United States, while others chose to retain their tribal membership and form of government. New lands were explored, new moves considered. As a result of the Treaty of 1856, the Stockbridge and Munsee moved to the townships of Red Springs and Bartelme in Shawano County. But the conflict between the Citizen Party and Indian Party was to have repercussions for many years to come.

RESERVATION

By the late 1800's, almost every Native nation in the United States had been assigned to reservations. The reservation land of the Stockbridge-Munsee was mostly covered with pine forest.

Farming was attempted but the land was sandy and swampy and so forestry became the base of the economy. Those valuable pine trees, however, were coveted by outside lumbering interests and led to further conflict between the Citizen and Indian Party factions of the Tribe. Provisions of previous Treaties and Congressional Acts did not provide adequate services, and poverty prevailed for most people. Treasured wampum belts and other cultural artifacts, craft materials and even traditional cl9thing were sold to collectors for a pittance.

An appeal to Congress resulted in the Act of 1871. Titled "For the relief of the Stockbridge and Munsee Indians," it provided an annuity for tribal people from the sale of 54 sections of their forested reservation lands. On the surface, it was to help solve the poverty of the tribal people and to also address the tribal in-fighting, even though it excluded people who had previously received land allotments. The underlying issue however, was the lining of pockets of the politicians and others who profited mightily by the timber profits from the lands they purchased in the 54 sections, an affair called the "Pine Ring".

In 1887 the General Allotment Act was passed by Congress. This divided up reservation lands and allotted portions to individuals, and were later patented and subject to taxation. This law applied to all Indian reservations, but was not new to the Stockbridge-Mu nsee Mohicans, whose lands had been allotted in earlier locations. The policy proved to be a very successful way of removing land from tribes by making it possible to deal with individuals who had little experience with private ownership. This happened on the Stockbridge reservation.

Subsequent Congressional Acts were still necessary to straighten out Tribal issues, and it wasn't until the early 1900's that all the allotments were complete , tribal membership restored, and the tribal funds apportioned. After the alloted lands became patented, some people who needed money sold their allotments to business dealers who wanted the forest for lumbering. Other dealers connived to get the land. Some families sold lakeshore property in order to make their mortgage payments on land they had purchased or to which they held title. Other Indian individuals lost their allotments because they were unable to meet tax or loan payments. Thus the tribe began to see its reservation land disappear and by the 1920's they were virtually landless, continuing in poverty, living on their formerly owned land as squatters or tenants. Hard times grew even worse during the Great Depression of the 1930's.

Some Americans were disturbed by the conditions to which Native people had been reduced and by the prohibitions that had been placed on them. Such a person was John Collier, an advocate for American Indian people. After he was appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs by Franklin Roosevelt, he prevailed upon Congress to pass the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA).

Tribal presidents Harry Chicks (above) and Arvid E. Miller (below) cared for their community and strived to make improvements for their people and land.

This law made it possible for Indian communities to get funds from the federal government to reorganize their tribal governments and retrieve some of the lands which they had lost. The IRA, along with the tenacity of dedicated tribal leaders during the hard years of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries - leaders such as Carl Miller and others - made possible the continuation of the Stockbridge-Munsee people as a nation.

It is ironic that the StockbridgeMunsee regained about 15,000 acres in the township of Bartelme. This western portion of the reservation lands had been clear cut, making it submarginal or useless and therefore eligible for repurchase for American Indian use.

Of the total 15,000 acres, however, only about 2,500 were placed in trust for the tribe, now officially called the "Stockbridge-Munsee Community, Band of Mohican Indians." Shortly after the mid-1930's, families began moving into the rough buildings that were once the headquarters of the Brooks and Ross Lumber Company. By the end of 1937, the tribe had a new constitution based on a Bureau of Indian Affairs model, and the Stockbridge-Munsee had a land base on which to rebuild homes for the people.

A new tribal council was elected with Harry A. Chicks as its president. The second president, Arvid E. Miller, was a leader of his people for twenty-six years. He was one of the founders of both the National Congress of American Indians and the Great Lakes InterTribal Council. In 1972, the remaining 13,000 acres of land were placed in trust, and tribal members received compensation (about eighty cents an acre) for lands that had been taken in eastern Wisconsin.

STOCKBRIDGE-MUNSEE TODAY

Today, on Shawano County Road A in northeastern Wisconsin, a new sign announces the reservation of the MOHICAN NATION. Circling the Many Trails symbol are the words

"Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians." The term "Mohican Nation" acknow-ledges the tribe's sovereignty and its government-to-government relationship with federal, state, county and township governments. The words "Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians" acknowledge the people's history.

The Stockbridge-Munsee Community is still located on this reservation in Wisconsin, although enrolled tribal members live in other parts of Wisconsin, the United States and the world. The reservation boundaries encompass the two townships of Red Springs and Bartelme; and currently include 17,150 acres of trust land, 7,584 acres of non trust or fee land for a total of 24,734 acres.

The Stockbridge-Munsee community has grown in mary ways over the past 60 years.

Some of the tribe's families live on trust land which is assigned to tribal members for their use. Others live on privatelyowned lands within the reservation boundaries, as do some non-Indians. Approximately half of the tribal population of about 1,500 live on or near the reservation.

Over the past eighty years, the Stockbridge-Munsee have not only survived but the community has grown in many ways.

First of all, the forests have returned, and with the forests so have deer, bear, waterfowl, wild turkeys and other animals. People have reported seeing a white deer and also a cougar.

Some early homes still provide shelter, including a few stone houses that are now on the National Historic Registry. However, mobile homes, apartments and more and more permanent homes continue to add to the housing opportunities on the reservation.

Apartments for the elderly and disabled are called the Moshuebee Apartments and the John W. Quinney Apartments, after ancestral leaders, and a new building to serve elderly meals and activities has been named the Eunice Stick Gathering Place.

Numerous structures are needed to house the tribal government, the tribal court, legal department, MOHICAN NEWS in the communications department, tribal administration and roads department. The Mohican Family Center features a full-size gym, exercise room, aerobics room, and youth center. In addition, a new comprehensive health and wellness center, including medical, dental and behavioral health facilities, opened in November of 2000.

The Pine Hills golf course has expanded to eighteen holes, and the clubhouse provides fine dining on weekends.

The original clubhouse has also been expanded and serves as a meeting hall and banquet facility.

The sandfilter/waste-water treatment facility will provide drinkable water to parts of the

reservation, and several roads are newly paved.

The pow-wow grounds have recently been refurbished, where the annual Mohican Nation Pow

wow is held during the second weekend in August to honor all veterans. Sweatlodges are used

frequently, at many sites on the reservation.

The North Star Mohican Casino Resort can be credited with much of the Mohican Nation's economic progress. The casino is the largest employer in Shawano County, and of the almost 500 employees, 400 are non-Mohican.

The casino also contributes to the economy of the county. Numerous buses arrive at the casino daily; deliveries of casino and bingo supplies, foods and beverages, fuel, paper products, cleaning supplies and other necessities attest to the economic contributions of the

casino in the area. The Little Star Convenience Store, Gas Station, and Car Wash provides employment and services.

Other tribal enterprises include Mohican LP Gas and a 5-unit strip mall which is currently under

constructions near the city of Shawano.

The children from the reservation attend school in the Bowler and Gresham Public Schools. Many high school graduates go on to college, technical school or a university. Tribal members hold degrees in law, medicine, education, engineering, architecture, science, fine arts and other disciplines. The StockbridgeMunsee Education Board oversees programs meant to encourage

students to progress in and advance their education.

THE LIBRARY/MUSEUM

Back in the early 1970's, Bernice Miller requested space from the Tribal Council for the purpose of preserving the papers and artifacts of her late husband, Arvid E. Miller.

An active historical committee, consisting of elders and anyone else interested in tribal history,

committed themselves to gathering everything that is known about the Stockbridge Munsee/Mohican people. A "ditto-machine" newspaper was started and shared community news for about ten years.

Gathering history required travel to homelands in the east. Since 1969 many historical research trips have been made. Traveling in caravans of autos or by bus, youth and elders

have visited the Mission House and burial grounds in Stockbridge,

Massachusetts. Many climbed Monument Mountain.

Research has been done in the Stockbridge Historical Room, the New York State Historical Library in Albany, the Huntington Library in New York City and in numerous other libraries and museums.

The research library includes: books, hand-written letters, notes, maps, photos, geneology records and more. The museum collection includes: baskets made of splints and birch bark, arrowheads, stone axes, war clubs and other original artifacts.

Through Repatriation artifacts returned to the Library/Museum include a wampum belt and

ceremonial pipes. Other repatriated items include wampum beads and a Communion Set. In 1993 the Tribe was fortunate to regain possession of a large volume Bible that had

been given to them in 1745 by the Chaplain of the Prince of Wales.

The Arvid E. Miller Memorial Library Museum is an excellent resource for students and scholars involved in research.

The Library/Museum welcomes visitors from near and far daily. It can also be visited on the tribe's website www.mohican.com.

TRIBAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION

The Stockbridge-Munsee Community has always maintained a connection to its Eastern

homelands and tribal members have continuously returned since the 1850's to protect burial sites or other cultural area or to pursue land claims. in 1999, this work was formalized by establishing a Tribal Historic Preservation office which routinely consults throughout our New York and New England areas. The office carries out duties under NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) to repatriate cultural items and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act to consult on federal construction projects that may impact cultural sites.

In 2011, the Tribe purchased 63 acres of land along the Hudson river to protect a culturally

sensitive Site. ln 2015 we were proud to formally establish a satellite Historic Preservation ofice on the campus of Russell Sage College in downtown Troy, N.Y. on Mohican homelands. The office reviews approximately 500 proposed construction projects a year, ensuring the Tribe's cultural perspective is heard in the planning process. We also contract with an archeologist to monitor sensitive projects and we have.